My Experience with COVID

By: Jacob Davis

I wanted to record my thoughts on my experience with COVID because I’ve had so many people reach out to me with prayer, love, questions and thoughts. This is my story.

I believe I first came in contact with COVID on January 23rd on a Saturday, and by the next Tuesday, January 26, the symptoms started. After I started running a fever along with some other mild symptoms, I took a COVID test on the 28th and it came back positive. I stayed at home for the rest of the week, lying in bed, running and breaking fever every day and laboring to breathe more and more. On February 4, I finally decided to go to the hospital. Ashlee, my amazing girlfriend who I love, also tested positive, but it didn’t affect her as intensely as it did me. She took me to the hospital and after going through the check-in process and assigning me a room, the doctors gave me two bags of convalescent plasma as well as Remdesivir. By the next day, I genuinely felt better so they released me to go home with a small oxygen tank. This decision proved to be costly, as within 12 hours of getting home, I could not breathe again and the tank was insufficient to keep up with my oxygen needs. Growing more and more uncomfortable and delirious, my buddy, Jeremy, called, and said that if I was not getting enough oxygen, there was no reason to stay home. That afternoon, Sunday, February 6, I went back to the hospital

People continued to send me a lot of prayers and spiritually uplifting messages, and I knew cerebrally that God was looking out for me, but I was having a really hard time. Part of the issue was that because I had been given the plasma, my body had turned into overdrive, trying to kill everything, not just the bad, so I continued to to run a fever and be ravaged by the disease, with my lungs being destroyed in the process.

It’s a little hard to describe what it felt like trying to breathe in that state. When your oxygen falls, it’s like exerting yourself in really intense exercise; you are desperately out of breath so your instinct is to breathe faster and faster, but there is no relief. I laid there, 24 hours a day, involuntarily suffocating myself.

Within a couple of days, my oxygen requirements increased to 15 liters and I started to wear a nonrebreather mask in addition to the nasal cannula I had been wearing the last few days. Even at the maximum supplemental oxygen, my blood saturation nosedived to 56 percent, which is a level dangerous to all of the organs in the body. It was at that point, the doctor came in and gave me a report that changed my life. He said that in my current state, he gave me a 50 percent chance of survival, but if my oxygen levels did not stabilize, over the next 12 hours, he would have to intubate me, at which point my chance of survival diminished to 25 percent.

And in that moment, when he told me that, life felt surreal. I started thinking about all the things I wanted to see my kids do and tell them and teach them that I hadn’t yet; there were so many things that I still had left to say to my loved ones. I wouldn’t see Jade graduate or get married one day, I wouldn’t see Jackson become a man; these things were being ripped away from me and there was nothing I could do. And being confronted with the decision to be put on a ventilator knowing that it increased my chance of dying, I all of the sudden realized that there are so many things in life that just don’t matter. They just aren’t important. We focus on so many other things and we don’t keep our attention in the present moment with those around us, and that’s really what’s important. We get so caught up in thinking about what others think and it is just completely irrelevant to everything, it has no value to our lives. There are so many beautiful and magical things about the creation that God, the creator, has given us that is so beautiful and perfect right in front of us but we have to focus for a minute to see it. The beauty is everywhere around us, and in everything. In that moment, when both death and life are palpable, you just realize that almost everything we worry about is self-induced and we create those anxieties unnecessarily. There’s a lot of simple beautiful things in life and, I just think if we just slow down a little bit, we can appreciate those things more.

So after wrestling with what the doctor told me, I think was able to find a place of solitude because I realized there wasn’t anything I could do about what was happening to me. I came to a place of peace with the 50 and possibly 75 percent chance that if was going to die, if God really intended to take me, then I was going to surrender and find the beauty in the experience of the sensation of death. I accepted that I wasn’t in control and death was very much a part of life. I came to be okay with it and I became curious about the journey of death. I decided to follow the experience of my consciousness going through the process of dying, whatever that was like, and I was going to enjoy the ride because life forced me to get to the point where I realized no one has control and there’s a sense of peace and beauty to it. I sent messages to my kids, my family and other loved ones for closure, and this stark, violent reality became my profound place of peace and serenity.

Along with the grim news, the doctor gave me an option. At my current 15 liters, if my oxygen kept falling below 88, a trip to the ICU was imminent, but my best chance to keep it above 88 was to lay on my stomach for 20 hours a day, as that position encouraged the highest level of oxygenation. Still numb from the news of my chances, I turned over onto my stomach along with the network of life saving tubes attached to me. Immediately, all of my old injuries began to scream. No matter what iteration — on the floor, draped over the bed, lying flat — I could not escape the pain; but when I got off of my stomach my oxygen levels would fall.

During the thick of that, when my mind alternated only between getting my next breath and coming to terms with the desperate, unrelenting pain, my dad called. The hospital wouldn’t allow friends or family in the unit to visit, due to Covid, so we FaceTime. He reminded me of when I was in track and he would see me hurting at a meet and still fight through. He said that this was one of those times that you have to bear down and push through the pain and believe in yourself. This conversation became a turning point, and I decided to fight.

I believe that the ability to discipline myself and persist came from three different parts of my childhood. First, from a very young age, my dad took my family and me to the Church of Christ in Mauriceville, close to where we lived in Orange. While I see the Church of Christ now as a very pure, vigorous and autonomous movement, as a child, I viewed it all as fire and brimstone, book, chapter and verse, lacking any charismatic elements to it. I felt constantly compelled by obedience, and there was a fear of God put in me to fight to resist my impulses at all times, or face the threat of burning in hell forever. Even though my perception was misguided, that kind of pressure to resist any and all human indulgence created a source of discipline of mind very early on.

The second part is that I grew up in a frugal, pragmatic household. I saw how hard my parents worked and I always felt badly asking them for things. As early as junior high, I hung around my peers and listened to them talk about their new Air Jordans or whatever, and I would wonder incredulously how they could possibly ask their parents to spend the kind of money for them to have things like that. What I didn’t realize is that they weren’t even necessarily asking or imploring their parents for these things, they were just being given that stuff. I realized that I needed choose between continuing to compare myself and desire validation through material things or accept that those thoughts never lead to any place healthy because I had no realistic means to obtain them. I chose to train my mind to reject and block those thoughts.

These two things lead to the third, perhaps, most significant experience, which is how I ended up going to college. I felt convinced, in junior high, that I wanted to get a scholarship to college because I couldn’t ask my parents to pay for it and I was sharp enough to know that if I went, it could possibly change my life. Due to the coach, pole vaulting at Orangefield gave me the highest likelihood of receiving a scholarship compared to any other sport so I decided to become a pole vaulter. Starting in junior high, I worked with a coach named Joe Hester, who was not only a great coach from a sport and technique perspective, but he trained our minds, and firmly instilled the ideal of belief in me. I asked him “If I do this, will I get better?” and he always answered yes. So I went out there and it didn’t matter if it was hard or I had to struggle, I would do it, because in my mind, I would get better and if I did the next thing, I would get even better. This, to me, logically concluded with a scholarship and a fulfilled promise of college. I never missed practice. He started training us on Thanksgiving Day and we vaulted six days a week until August, and that is how I lived for years. In hindsight, I don’t know why my mind chose to be disciplined in those situations while the minds of others didn’t, but I just maintained a perspective of believing that if I took a rock and pounded it hard enough and long enough, it would eventually break and there would be hope on the other side.

I laid on my stomach for 18 to 20 hours a day for many, many days, in pain, unable to sleep, trying to breathe, trying to stay alive. The doctor said that the vast majority did not have the capacity to adhere to the hours and hours stomach lying, and yet it was this very ability to persevere in that position for days that would possibly saved my life.

My oxygen levels slowly started improving over the next four to five days. People continued to pour prayers and encouraging texts into my heart and I felt so thankful for all of the people wanting to lift my spirits. Most of the days, hours and minutes spent laying there, alone in the hospital, were genuinely terrible. But the constant encouragements and kind words fueled my will to take another breath, endure another ache. I even received comic relief in ways I didn’t expected.

After my oxygen saturation stabilized and I was able to lay on my side, I started to develop a pretty serious cough around February 11. My sternum was bruised significantly from laying on my stomach and coughing for so long and it took me three or four days to really sort through that pain. By the end of the week around the 13th or 14th, my lungs showed significant improvement. I was set to be discharged the next day, but as these things seem to go, I started to run a fever again on the 14th and it turned out that I contracted something new. My fever started pushing 103 degrees and blood tests showed that my white blood cell count was very elevated and my kidneys were functioning at 50 percent. I contracted bacterial pneumonia and my immune system was turning on me.

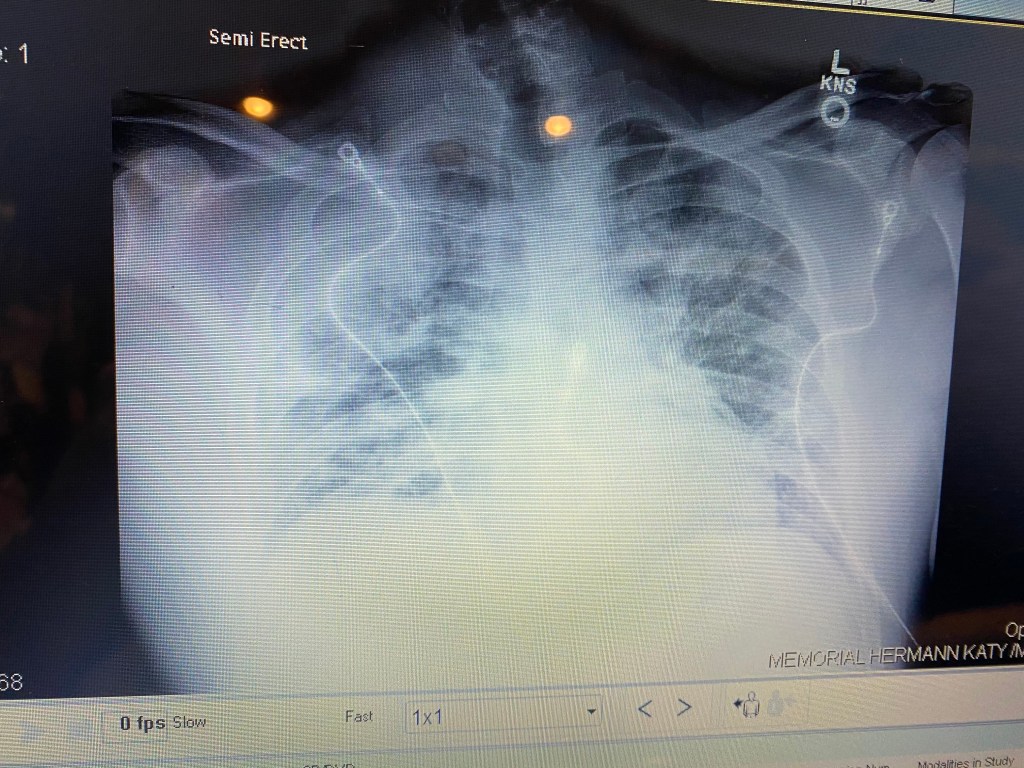

And so the battery of chest x-rays and blood tests commenced again. The veins in my arms were already destroyed. It took them over 12 tries to hit a vein one time because they had already exhausted both of my hands, forearms, elbows and the top sides of my arms. I estimate that during the time I spent in the hospital, my arms were stuck over 200 times, with more than seven IVs put in me because a few of them blew through and others just got old and had to be replaced.

But you know, I would tell the nurses, “I believe in y’all and y’all do what y’all need to do and you stick me all you want because when you stick me, it makes me feel alive.” Sometimes, a nurse named Angela who was from Nigeria, would draw my blood. We laughed and joked and sometimes she would sing Nigerian hymns while trying to find an undiscovered place to poke. After a while, I could sing them with her. I actually got a little recording of it, it was just spontaneous and really genuine and freeing to have someone there with such an open, generous spirit. I told her “You’re a really good mama” and she responded “Yes I am! But when my kids don’t listen to me, they get that switch on their booty. Did your mama do that to you?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Within a couple of days, the pneumonia really escalated so they started dripping some really strong antibiotics and performed every blood and germ test they could think of. Over the next few days, the antibiotics started working and my white blood cell count started dropping along with my other elevated statistics. Even with the anxiety, uncertainty and fear constantly knocking, I tried to be hopeful because I was so thankful for what the doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists and staff did for me.

On the afternoon of February 19, I was discharged from the hospital. I could not even stand without a walker, I had not shaved or had a bath in over two weeks and could hardly use the restroom on my own, but I was alive and that was more than enough.

I’ve always been kind of free spirited and laid back but I think one thing this experience has done to me, very quickly, is that I feel completely freed from the inhibition to tell people how I feel about them. Before I went through all of this, I hesitated to tell someone that I loved them or that I was proud of them and resisted being in the present moment with people, but I feel now that these connections are one of the very few things in life that actually matter; it’s letting people around you know that their existence in the world means something and what they do is important.

All that to say, I love you, thanks for reading, and I hope it blessed you.